Continued from “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day, part 1”

Charles Longfellow, the eldest son and child of poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, left the family’s home at Craigie House in Cambridge, Massachusetts without explanation or a “good-bye” on March 10, 1863. He traveled to Washington, D.C. and initially attached himself to a Massachusetts artillery battery.

Clad in a new uniform and boots, 2nd Lt. Charles Longfellow of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry Regiment posed for a photographer sometime in early spring 1863. His father, poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, spent $779 .75 to fully outfit Charley and buy him two horses. (Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site)

His father was none too happy, but ultimately accepted his son’s decision to join the war effort. By April 1 Charley was a second lieutenant in the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry Regiment.

Felled by “camp fever” in early June 1863, Charley gradually recovered in Washington, D.C. under the care of his father and Reverend James Richardson, a U.S. Sanitary Commission member. Both men treated Charley as directed by Dr. Meredith Clymer, “the surgeon in charge of all sick and wounded officers” in the District.

Longfellow took Charley to Massachusetts in late June to join the other four children at the family’s Nahant summer home. Charley got better, then left to rejoin his regiment on August 14. Venturing from Washington with a wagon train’s escort, he found the 1st Massachusetts camped “near Warrenton” and quickly resumed military life.

Commanded by Col. Horace B. Sargent, the regiment belonged to the 1st Brigade (Col. John P. Taylor), 2nd Cavalry Division (Brig. Gen. David McM. Gregg). The brigade broke camp on Saturday September 12 and reached “White Sulpher springs that night,” Charley recalled. Dawn Sunday found the troopers headed toward Culpeper.

“About noon the advance guard met the rebs whom they drove clear before them through Culpepper [sic] a little beyond which they made a stand,” he said. Ordered to support an artillery battery, the Bay State troopers found “the shot and shell were flying over our heads by this time pretty lively and the first thing I knew I saw a 12 lb shot coming bounding along.”

The solid cannonball “made two jumps in front of us and then went zip close by my leg” and struck Sgt. Charles A. Read “below the knee[,] taking his leg off,” Charley reported. One shell burst “so close to my face as to make me feel the blast of hot air.”

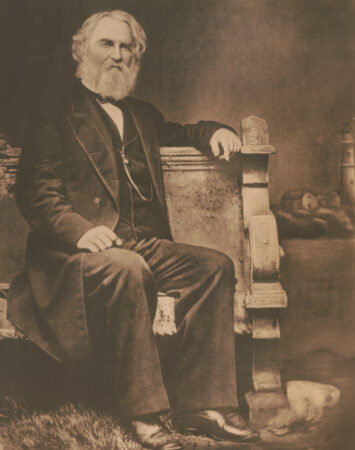

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow grew a full beard to hide the scars caused when he was burned while smothering the fire that engulfed his wife, Fanny, on July 9, 1861. (Library of Congress)

The regiment’s quartermaster, Charley performed various duties as the armies sporadically sparred in Virginia that fall. On Thursday, November 26, the 2nd Cavalry Division crossed the Rapidan River at Ely’s Ford as Maj. Gen. George G. Meade went after Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia.

The ensuing Mine Run campaign took the 2nd Cavalry Division across the Wilderness toward points south. On Friday Gregg advanced “rapidly through a gloomy and forbidding forest toward the town of Gordonsville.”

His vanguard collided with “Confederate cavalry pickets” at the clearing around New Hope Church. Union troopers dismounted, chased the retreating Johnnies, and soon ran into Southern infantry. Up came Union artillery to oppose the enemy’s batteries, the Johnnies finally stood their ground, and Taylor went forward to learn exactly what his cavalry faced.

Also reconnoitering the Southern lines, Charley encountered Taylor. “The two officers walked carefully through a thicket, emerged briefly into a small clearing, and headed” for nearby trees. “A ragged volley swept toward them,” and a bullet struck Charley. He fell forward, struck the ground, and yelled, “I’m shot!”

Taylor carried Charley to safety. A quick exam revealed that a bullet, “presumably from an Enfield rifle,” had punched into “him under the shoulder blade, twisted through the body, nicked his spine, and emerged on the other side.” Doctors would discover that the bullet “had missed his lungs and arteries” and also missed his spine by an inch or so. The army started him on the long road to recovery.

The door bell ringing at Craigie House at dinner time on Tuesday, December 1 announced “a telegram from Washington stating that Charles had been severely wounded,” Henry Wadsworth Longfellow told his journal. Abandoning supper, he and his son, Ernest, left immediately for Fall River, Massachusetts, where they boarded the steamer for New York City.

“Stormy night, and severe gale on the [Long Island] Sound,” Longfellow noted.

He and Ernest promptly reached Washington, D.C., but not until December 5 did Charley and 15 other wounded Union officers rattle into the railroad station aboard “a straw-filled baggage car.” Not until 8:30 p.m., Tuesday, December 8 did all three Longfellows leave for home aboard a Baltimore & Ohio Railroad train.

Shot and wounded during a fight around New Hope Church during the Mine Run campaign, the recovering Charley Longfellow looked weary when photographed in December 1863. (LOC)

Father and sons reached Craigie House around 10 p.m., Wednesday, and Charley settled into his long recovery surrounded by his worried father, adoring and attentive sisters, and other relatives and friends who called.

His father caught a bad cold, but on December 18 happily reported to abolitionist Massachusetts Senator (and close friend) Charles Sumner that “Charley is doing well; and getting stronger day by day. He whistles, and sings, and is in very good spirits. He has already begun to order things for his next campaign!”

No one, least of all Charley, realized that his war was over. His wound would force a medical discharge upon him, but Henry Wadsworth Longfellow did not know as Christmas approached that his oldest boy was safely home from the war.

Cambridge church bells bonged and donged on Friday, December 25. Their clanging message penetrated Wadsworth’s melancholy; the poet recalled that first Christmas, when a savior promised by God was born in a Bethlehem stable to bring peace and joy to humans. Taking pen in hand, Longfellow poured his pent-up fears — for his own beloved son and his beloved country shattered by a bloody Civil War — into a poem.

“I heard the bells on Christmas Day, their old familiar carols play,

And wild and sweet the words repeat of peace on earth, good-will to men!

“And thought how, as the day had come, the belfries of all Christendom

Had rolled along the unbroken song of peace on earth, good-will to men!

“Till ringing, singing on its way, the world revolved from night to day,

A voice, a chime, a chant sublime of peace on earth, good-will to men!

“Then from each black, accursed mouth the cannon thundered in the South,

And with the sound the carols drowned of peace on earth, good-will to men!

“It was if an earthquake rent the hearth-stones of a continent,

And made forlorn the households born of peace on earth, good-will to men!

“And in despair I bowed my head; “there is no peace on earth,” I said;

“For hate is strong, and mocks the song of peace on earth, good-will to men!

“Then pealed the bells more loud and deep; God is not dead; nor doth he sleep!

The Wrong shall fail, the Right prevail, with peace on earth, good-will to men!”

Sources: Andrew Hilene, Charley Longfellow Goes to War, III, Harvard Library Bulletin XIV, spring 1960; The Letters of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, vol. 4, Andrew Hilene (ed.), Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1972; Brig. Gen. David McM. Gregg, War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Vol. 29, part 1, No. 90, pp. 806-807

—————————————————————————————————————–

Be sure to like Maine at War on Facebook!

—————————————————————————————————————–

If you enjoy reading the adventures of Mainers caught up in the Civil War, be sure to get a copy of the new Maine at War Volume 1: Bladensburg to Sharpsburg, available online at Amazon and all major book retailers, including Books-A-Million and Barnes & Noble.

If you enjoy reading the adventures of Mainers caught up in the Civil War, be sure to get a copy of the new Maine at War Volume 1: Bladensburg to Sharpsburg, available online at Amazon and all major book retailers, including Books-A-Million and Barnes & Noble.

Passing Through the Fire: Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain and the Civil War (released by Savas Beatie) chronicles the swift transition of Joshua L. Chamberlain from college professor and family man to regimental and brigade commander.

Drawing on Chamberlain’s extensive memoirs and writings and multiple period sources, the book follows Chamberlain through the war while examining the determined warrior who let nothing prevent him from helping save the United States.

Order your autographed copy by contacting author Brian Swartz at visionsofmaine@tds.net

Passing Through the Fire is also available at savasbeatie.com or Amazon.

—————————————————————————————————————–

Brian Swartz can be reached at visionsofmaine@tds.net. He enjoys hearing from Civil War buffs interested in Maine’s involvement in the war.